Shirley longed for acceptance and belonging in her new American life but she didn’t exactly fit in. Instantly, I identified with Shirley Temple Wong. For the first time in my young life, I read a story where the main character was Asian. Reading that book was a profound experience. I’m reminded of the time I read In the Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson. What would it have been like to read about an Asian American girl whose experiences matched my own? How would my thinking have changed to know there were other girls like me - who struggled with the same issues of cultural identity and belonging? But books rarely mirrored my experience of life as an Asian American. I like to think that reading Mindy’s story as a child would have given me the confidence to embrace my feelings of “otherness.” Mindy is fully American yet still holds onto her Korean heritage and culture.Īs a child, I loved to read.

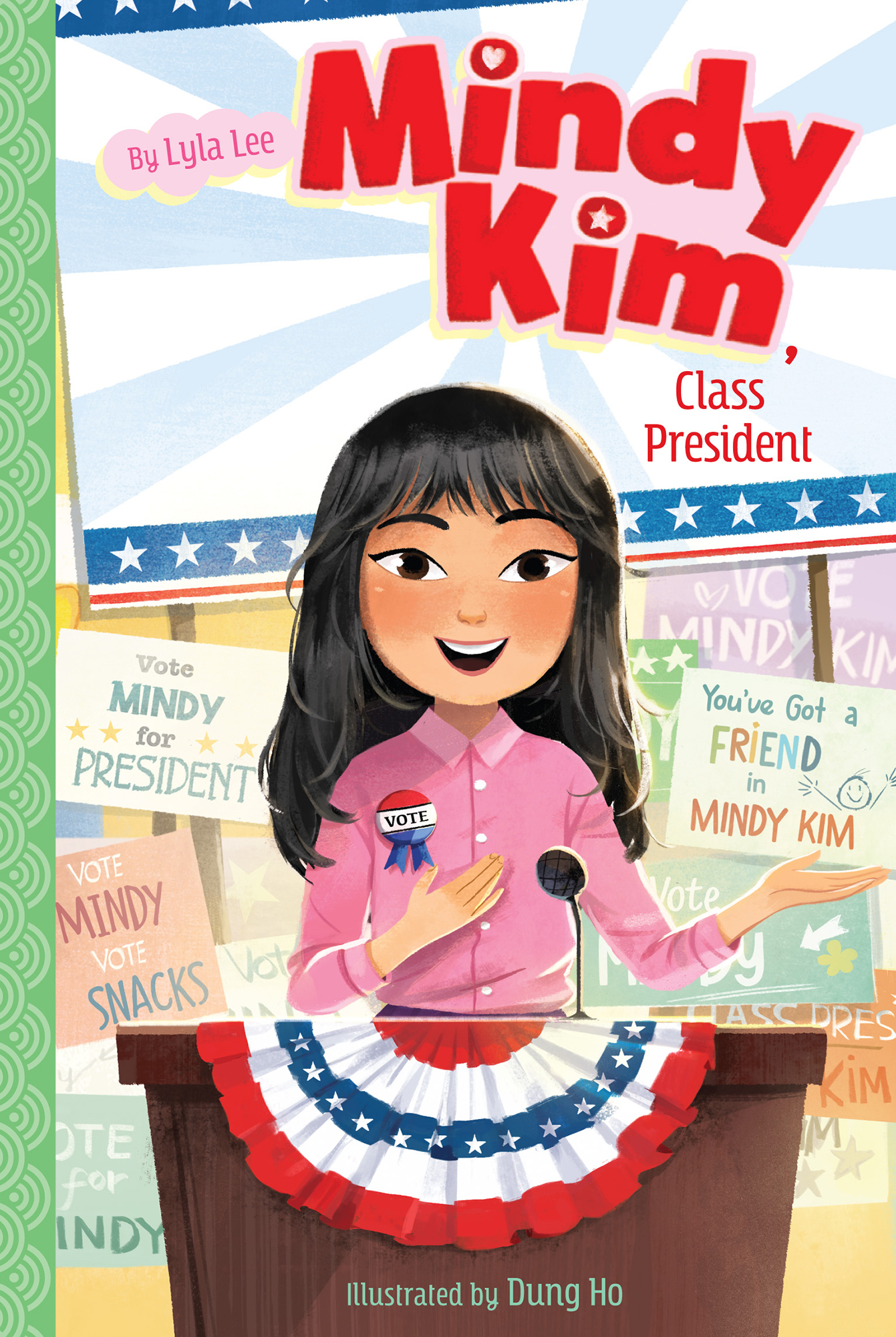

In a brief 82 pages, the strange and often alienating experiences of my childhood were suddenly validated. There it was, in print, the story of a little girl who looked like me, talked like me, and thought like me. I loved reading about Mindy and understood the significance of this book. Notably, Mindy experienced racial micro-aggressions not only from her peers but from authority figures as well. She even Anglicized her name from Min-Jung to “Mindy,” and understood how this assimilation made people feel more comfortable. Like me, Mindy called her dad “Appa,” the Korean word for “Daddy.” Like me, she noticed when no one looked like her in the school yard. How many times had I experienced a similar moment? Too many times to count!Īs I kept reading, I began reflecting on my own experiences as an Asian growing up in America. Immediately, I was transported to my childhood. When she opens her lunch box in the cafeteria, everyone thinks her food is weird and smells bad. Mindy, a Korean American girl, moves to a different school and tries to make new friends.

When I started reading Mindy Kim and the Yummy Seaweed Business, I quickly found myself identifying with the 7-year old protagonist. But the queries inevitably came up in other times and places: what is that? Why does your food smell so bad? Don’t you eat anything normal? In the face of such questions, my embarrassment knew no bounds. My family ate different kinds of food, too.Īt school, I escaped the shame of eating Korean food by eating the hot meal provided by the lunch ladies. Some people told me directly, you’re different. As a Korean American growing up in a predominantly white town, I understood what it meant to be an outsider.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)